From the Detroit Free Press:

The long-awaited M-1 Rail project has a new route map, a promised spring groundbreaking and soon, maybe, a new name.

The long-awaited M-1 Rail project has a new route map, a promised spring groundbreaking and soon, maybe, a new name.

Naming rights will be sold as part of the marketing plan for the $140-million M-1 Rail line — so look for it to be called anything from the Little Caesars Express to the Quicken Loans Choo-Choo.

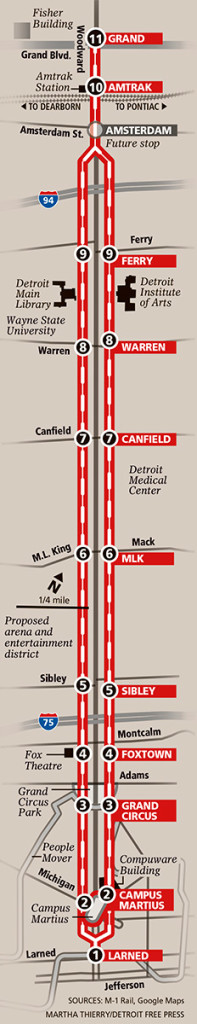

Naming rights for the urban rail line — like in Cleveland and other cities — could bring $1 million or more to help pay for the line, slated to run 3 miles along Woodward from Jefferson Avenue downtown to Grand Boulevard in New Center. The first passengers could be boarding by fall 2016, said Paul Childs, chief operating officer of M-1.

The broader question remains whether M-1 will run as a limited, stand-alone operation — much as the People Mover has looped around downtown since the 1980s — or lead to the build-out of a regional system that could run north to 8 Mile Road or even Pontiac and include rapid transit buses.

“I think it’s absolutely just the first portion of a regional transit network. I think this really gives us the foundational link people are going to build on,” said Matt Cullen, CEO of M-1 Rail. “We really think it’s the right project at the right time for Detroit. The hard work and the pain will be worth it.”

The broader vision still needs funding. A plan from the new Regional Transit Authority to ask voters for a fee or tax to pay for it was delayed last month until 2016, which could give the public time to experience the M-1 line in action. Depending on what sort of larger system is designed, stretching the line farther north — and east and west — could cost from hundreds of millions of dollars to more than $1 billion.

“I hope that we can move beyond this first phase,” said Harriet Saperstein, chairperson of the nonprofit civic group Woodward Avenue Action Association. “The downtown portion is important, but it’s only one part of the public transportation system we need all along Woodward Avenue.”

So far, the M-1 Rail project has raised about $132 million from a patchwork of corporations, foundations, nonprofit agencies and government sources. It needs another $10 million or so, with potential sources already identified for about $6 million of the gap, said Laura Trudeau, a managing director with Kresge Foundation who works closely with the M-1 effort.

First stop?

For workers and residents of greater downtown, M-1 promises connections among different sites and at least a partial solution to the parking shortage in the increasingly crowded areas. The streetcars will run curbside with the flow of traffic.

Graig Donnelly, director of the Detroit Revitalization Fellows program based in the TechTown building near Wayne State University, is looking forward to riding the line. He said he drives his car to downtown meetings now but will switch to the streetcar when it opens.

“Given where my office is located and how close we’ll be to that amenity, I’ll just hop on the M-1 Rail,” he said. “It’s a no-brainer. It’s a quality-of-life thing.”

Donnelly sees another benefit: greater networking possibilities from running into acquaintances on the new transit line. “I think that those are unplanned things that add richness,” he said.

Supporters hope that richness of experience and other selling points, such as economic development gains for neighborhoods along Woodward, will add up to a compelling case for voters to approve future public funding for a regional system.

The idea over the years has been to use the M-1 Rail as a demonstration project that would win support for a wider network. There are some signs among regional officials that building out a broader system could gain support if it operates as a less-expensive rapid transit bus line, rather than adding more and costly light rail.

Not everyone is a fan of big new public transit systems in metro Detroit. Republican legislators in Lansing have balked at providing any funding, and some neighborhood activists worry that real estate along the M-1 route will grow so pricey that lower-income residents will be forced to move.

But proponents argue that new, higher-priced transit-oriented development is exactly what tax-strapped Detroit needs and a key reason for building M-1 in the first place.

A different path

The M-1 project’s financing and organization are unlike most, or perhaps any other, big city transit systems. M-1 will operate as a private nonprofit, with its operations and maintenance outsourced to a private vendor yet to be chosen. This is in contrast to other systems that are generally administered by city departments of transportation.

Financing, too, is nontraditional, with major backing coming from a mosaic of private business leaders, the Kresge Foundation and other foundations, the city’s Downtown Development Authority and the federal government, along with multiple other sources.

“It’s not an ideal way to build public infrastructure, but it seems to be our best shot at getting transit in the near future,” said Megan Owens, executive director of the nonprofit civic group Transportation Riders United.

The hybrid structure and financing model is a legacy of the tortuous trail M-1 backers have navigated from the beginning.

The project dates to 2008, when John Hertel, a former state legislator and general manager of the suburban SMART bus system, was asked by regional leaders to explore the possibility of a new regional transit system.

Hertel knew metro Detroit had suffered multiple failures during the past 40 years to create such a system due to regional animosities and city-suburban conflicts. So to jump-start a regional system, he recruited the Ilitch family, Compuware founder Peter Karmanos, Super Bowl XL Host Committee Chairman Roger Penske, WSU and other deep-pocketed individuals and institutions to pledge support for a 3.2-mile streetcar line along Woodward Avenue.

■ Related: Roger Penske touts M-1 Rail project as Detroit’s ‘home-run project’

In 2010, the M-1 project was merged into ambitious larger plans to create a faster transit system from Detroit to the city’s border with Oakland County. But those plans fell apart in 2011, and it appeared for a time that the idea of a streetcar on Woodward was dead.

Now led by Cullen, a former General Motors executive who heads up businessman Dan Gilbert’s Rock Ventures, the private and nonprofit investors in M-1 resurrected the original concept of the streetcar line along Woodward for greater downtown. That’s the concept now close to groundbreaking with some initial utility relocation work already begun downtown.

Childs, the project’s COO, said the money already raised will be enough to build and operate M-1 for 10 years. Besides construction funding, money is available for operations through several sources: fares, the naming rights and an operational fund that will benefit from private and public support.

In Cleveland, the city’s bus rapid transit line along Euclid Avenue was named the HealthLine after it received sponsorships from the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospital on the eastern end of the line. In Detroit, Owens of the transit riders group said that sort of name is preferable to a more blatantly commercial sponsorship.

That will be decided sooner rather than later. But whether this long-delayed system, with its unique structure and financing, becomes the first component of a broader regional transit network is a question that will take longer to answer.

Source: http://www.freep.com/article/20140309/BUSINESS06/303090063/M-1-Rail-transit-Detroit-streetcars