From The Detroit News:

The number of train-vehicle crashes has spiked in recent years and the blame is being squarely put on one factor: driver error, including distracted driving.

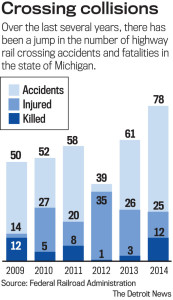

Michigan has the 10th highest collision rate in the country with 78 crashes last year: 12 people were killed and 25 were injured, according to recent figures released by the Federal Railroad Administration.

In 2013, there were 61 crashes, three fatalities and 26 were injured. From 2013 to last year, those killed in the state in railway crashes is up almost 35 percent.

Increased regulations and safety measures over the last 40 years contributed to a steady decline in the number of accidents nationally, but experts say this recent uptick in Michigan and nationwide is due to multitaskers at the wheel and distraction from smartphones and electronic devices.

Nationally, the numbers of train collisions are up as well. The federal railroad agency now says every three hours in America a person is struck by a train. In 2014, there were 267 fatalities from crashes, compared with 231 in 2013, a rise of about 19 percent. Trespasser incidents (meaning pedestrians on the tracks) accounted for 526 killed last year — up 22 percent from 2013.

Nationally, the numbers of train collisions are up as well. The federal railroad agency now says every three hours in America a person is struck by a train. In 2014, there were 267 fatalities from crashes, compared with 231 in 2013, a rise of about 19 percent. Trespasser incidents (meaning pedestrians on the tracks) accounted for 526 killed last year — up 22 percent from 2013.

“The sad truth is that nearly all these deaths are preventable,” said Sam Crowl, state coordinator of Operation Lifesaver, a nationwide nonprofit promoting railroad crossing safety and trespassing prevention. People are just in too much of a rush, he said.

“Impatient drivers just don’t care; they are going to hurry across,” said Crowl, a former locomotive engineer and Conrail safety official.

The nonprofit launched a campaign on social media including Twitter with reminders to pay attention when coming to a train crossing. The campaign stresses “Around train tracks, stay focused — stay alive.”

48-year-old first fatality of year

This month, a 48-year-old woman in Wexford County, about 20 miles south of Traverse City, became the state’s first train collision fatality of 2015.

Around 10 a.m. March 3, Kathryn M. Paddock of Liberty Township was traveling on East 14 Road when she struck a northbound train and was killed instantly. Police said neither speed nor alcohol were factors.

“She lived a mile and a half down the road,” said Wexford County Sheriff’s Lt. Greg Webster. “She actually ran into the train. There were no skid marks.”

Sheriff Deputy Arjay Schopieray added that weather could have played a role in the accident. “At the time the accident occurred, there was freezing rain and sleet,” he said.

This was not the first time train tragedy struck the family. In June 1994, Paddock’s brother-in-law Brian G. Paddock collided with a train at the same railroad crossing and also was killed. He was 32.

The crossing is “well marked,” Webster said, with a crossbuck sign that tells drivers to yield if a train is approaching.

“It was the same with the brother,” said Webster, who investigated both incidents. “They just didn’t expect the train to be coming.”

Perhaps the state’s worst crash in recent memory was the fatal car train crash in Canton Township in July 2009, when five young victims, including two teenage brothers, were killed.

The driver of the Ford Fusion passed at least two cars stopped at the Hannan railroad crossing before maneuvering around the safety gates into the train’s path.

“The gates were down and the car swerved around to try to beat the train,” Crowl said. “Engineers will tell you: We see people trying to race their way across all the time. All it takes is one person to think they can outsmart the train. And they can’t.”

The Michigan Department of Transportation has an annual safety program that installs enhanced warning devices at crossings where it is warranted. Nothing, however, takes the place of drivers’ heeding safety warnings.

“MDOT concurs with Operation Lifesaver that train/vehicle crashes can occur because of driver impatience or being distracted,” said MDOT spokesman Michael Frezell. “We encourage drivers to be safe at every railroad crossing and expect a train anytime. And we stand behind Michigan Operation Lifesaver’s campaign to ‘look, listen, and live’ at every crossing.”

After a recent string of deadly crashes involving vehicles and commuter trains nationwide, congressional lawmakers called for the federal government to boost the safety of railroad crossings.

But, on Wednesday, Bill Shuster, R-Pennsylvania, chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, said in news reports that Congress should avoid a “knee jerk reaction.”

“It’s almost always not the railroad’s fault that somebody gets hurt or some accident occurs at a grade crossing,” he said. “It’s the passenger vehicle or the truck trying to run a crossing when it should stop.”

On Saturday in a Louisville, Kentucky, neighborhood, authorities say a car containing four people was hit after train signals were disregarded. Two people were killed and two were injured. The vehicle was dragged about a half mile.

The Kentucky accident was the fourth serious train crash in the country in less than two months.

A Feb. 3 crash on a railway crossing just north of New York City involved the driver of an SUV who police said mistakenly thought she had more time.

According to officials, the flashing lights at the crossing activated 39 seconds before the train arrived, and the gates came down seconds later. After spotting the SUV on the tracks, the engineer hit the emergency brake and the train slowed from 58 mph to 49 mph up to the point of the collision.

Witnesses said the crossing gate came down on the rear of the Mercedes SUV. Ellen Brody, the driver, got out, most likely to inspect the damage, and then got back in her vehicle. After a brief pause, she drove forward and was struck by the train. She and five people on the train were killed.

“The collision was due to human error,” Crowl said. “It was completely preventable, and that’s what makes education and enforcement so important.”

“By getting out and getting back in, she wasted precious seconds,” Crowl said. “The gates are made of a very weak material; they are meant to break off. We tell people if they are on the tracks when lights start flashing, keep driving through.”

The collision remains under investigation.

Investigator blames law breakers

At age 22, Crowl became the youngest engineer on the Pennsylvania railroad. He spent 45 years as locomotive engineer; for 15 years he served as safety superintendent for Conrail’s entire system. As such, Crowl has investigated hundreds of collisions and fatalities.

Without exception, “All of the incidents would not have happened if people complied with the law,” he said.

As data recorders and cameras on trains almost always bear out, the consistent determining factor is not faulty warning lights or crossing gates, but poor judgment on the part of a driver or pedestrian. The federal railroad agency says 94 percent of train-vehicle collisions can be attributed to driver error, which includes distracted driving.

The speed of a train is rarely a factor in train crashes, Crowl said. But drivers often misjudge the speed of an oncoming train.

“People don’t understand how hard it is to judge the speed of a train coming at you,” Crowl said. “It’s often hard to tell the difference between the speed of a freight train at 40 mph or a passenger train at 110 mph.”

People also think they can hear easily hear a train coming. Because modern railcars glide with low friction, “trains can be incredibly quiet, especially when traveling on level tracks,” Crowl said.

Little engineers can do to stop

It’s not easy to stop a train.

An average freight train traveling at 55 mph takes a mile or more to stop, which is the equivalent of 18 football fields.

For an engineer to see a car or person on the tracks and know the train cannot stop is the most helpless feeling imaginable, said Crowl, who was involved in two fatalities during his career.

“It’s horrible because there is nothing we can do. We don’t have a steering wheel. All you can do is put the brakes on.”

In 2004, a Bloomfield Hills school bus on its way to pick up students was hit by an Amtrak passenger train bound for Chicago at the railroad crossing at Kensington and Opdyke.

“The only person on the bus was the driver,” Crowl said, “but the engineer didn’t know it. He told me that after he stopped the train about a mile down the tracks he sat there wondering how many kids he might have killed.

“After that, he walked off the job and never came back to work. He was about 50 years old at the time, but that was it for him.”

Last weekend in Manton, train crash victim Kathryn “Kathy” Paddock was remembered as an adoring mother to her daughter, Elizabeth, and loving wife to husband Jay. She worked part time at Bath and Body Works, and found great joy in being a nanny for a local family. She also loved researching and testing out new cupcake recipes, or occasionally going out on a “girls night” with close friends.

Jay Paddock, Kathy’s husband and Brian Paddock’s brother, said he was too grief stricken to be interviewed. But he stressed in an email to The Detroit News: “There was no wrongdoing on the part of anyone or anything with the train. My wife either did not see the train in time or did not try soon enough to stop with the weather conditions.

“There is a yield sign at the crossing and we have lived and driven over these tracks enough to know we need to look for trains there. My brother was killed at the same crossing June 9, 1994. He drove over the tracks without looking or slowing down. It was his fault he was hit, not the railroad’s.”

Michigan crashes

A sample of accidents involving trains:

Dec. 5, 2001: Two State Police troopers rushing to help an officer who radioed for assistance tried to beat a train to the Scott Lake Road crossing in Waterford. Witnesses say the patrol car passed six vehicles stopped at the railroad crossing, ignored the flashing lights and the closed gated and drove into the path of an oncoming freight train.

June 4, 2004: A railroad gate failed to lower in time to stop a Charlotte woman from driving into the path of an oncoming train in a collision that killed her and her 15-year-old daughter.

July 4, 2006: A 70-year-old man was killed in a train-car collision at 15 Mile and Groesbeck in Clinton Township. The flashing lights were obstructed, the red lights were operating at partial power, and the backgrounds to the lights were faded, all of which contributed to the crash.

Feb. 25, 2009: A 38-year-old Holly man driving a pickup appeared to deliberately drive his truck into the side of a freight train on Fish Lake Road shortly after 6 a.m. The victim, who was dead at the scene, was the focus of a domestic violence report filed just minutes earlier and a mile away, police said.

Sept. 14, 2011: A 19-year-old motorist was killed when his vehicle was struck in Hartford Township by an Amtrak train carrying 72 passengers from Chicago to Grand Rapids. Authorities said the crossing had working lights and barriers.

Oct. 7, 2013: A 45-year-old woman died after driving around a railroad crossing gate and being struck by an Amtrak train in Shiawassee County’s Vernon Township.

Jan. 1, 2014: A 19-year-old Pontiac man driving a truck went around a crossing gate in Pontiac shortly before 10 p.m. when he was struck by a Chicago-bound Amtrak train. The man was taken to an area hospital where he was listed in stable condition.

Source: http://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/local/michigan/2015/03/20/michigan-train-car-crashes/25058717/